Wine Flicks | Tony Bracy

25 April 2020

It seems a long time since feel-good wine movies were all the rage at the local cinema. But if you ignore some ‘golden oldies’ like This Earth is Mine (1959), The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969), Fine Gold (1989) and The Year of The Comet (1992), the rush of wine movies was a reasonably contemporary thing.

More recently there were also wine documentaries including Somm (2012), A Year in Champagne (2014), Sour Grapes (2016) and Tin City (2019), all worth seeing, but I’m not sure whether the 2017 French wine drama Back to Burgundy was ever released here.

If you are interested in something completely different you might like to try the new Netflix movie Uncorked if and when it becomes available here. Released in the USA on 27 March and written and directed by Prentice Penny, it tells the story of Elijah, a young black man (Mamoudou Athie), who upsets his father Louis (Courtney B. Vance) when he pursues his dream of becoming a master sommelier instead of joining the family BBQ business. However, for now let’s focus on what we have already seen at the cinema.

The first of the more modern wine movies was Sideways in 2004 which was followed in 2006 by A Good Year and Bottle Shock two years later and that four-year period was a mere twelve to sixteen years ago. As the memory of those feel-good movies lives on for many of us, I thought I would revisit some of the notable moments in each of them to refresh a few remembrances, including my own. And thanks to scripts.com and script-o-rama.com for making so many great wine words possible. It has added soul to the heart of this piece.

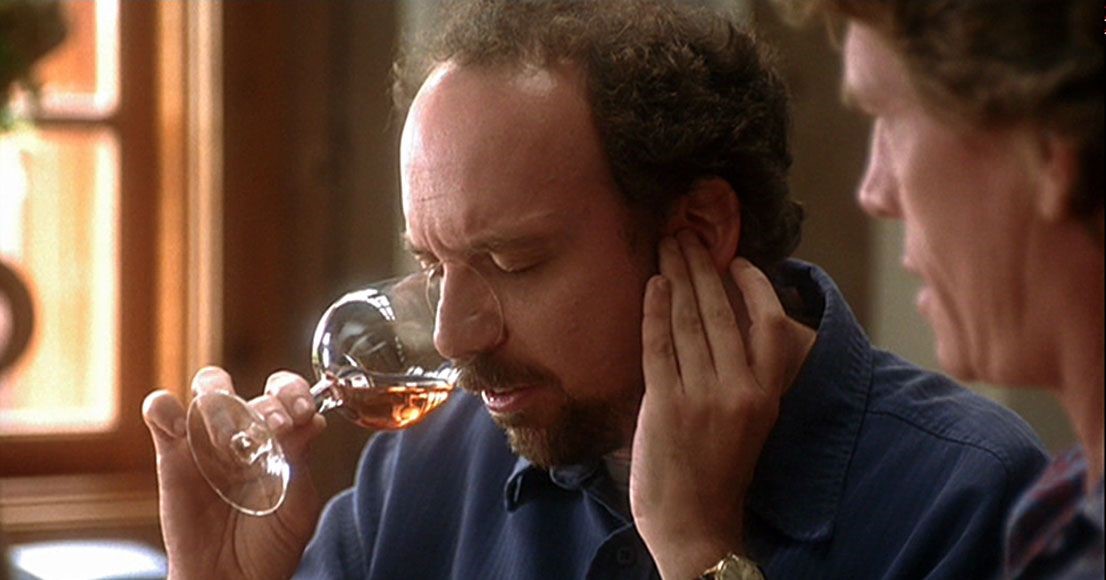

Sideways

PICTURED ABOVE: MILES & JACK WINE TASTING

It is hard to list your favourite wine movies without including Sideways, an independent film with screenplay by Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor based on the 1999 novel by Rex Pickett. The story featured a “boys away” week in the Santa Ynez Valley in California’s Central Coast Santa Barbara wine country by friends Miles, a failed writer with a novel awaiting a publisher’s verdict played by Paul Giamatti, and Jack, a washed-up actor played by Thomas Haden Church, in the week prior to Jack’s wedding. The two friends had almost completely different objectives for their trip: Miles to taste fine wines, particularly Pinot Noir, and to play golf; Jack to chase women. And, for better or worse, both friends succeeded.

Many movies have inconsistencies and one of those presented in Sideways is that Miles, a Pinot Noir tragic, has a bottle of Bordeaux wine – a Cheval Blanc ’61 Saint-Émilion Premier Grand Cru Classé “A” – as a trophy. This great vintage of Cheval Blanc was a blend of 58% Cabernet Franc and 42% Merlot which could not be more different to Miles’ favourite Pinot Noir. Although it was 43 years old in 2004 and arguably past its prime, Cheval Blanc was then and is still an expensive wine: the more recent 2010 vintage sells here for around $A2,300 a bottle! Miles’ conflicting dislike for Merlot was reflected in the scene outside the Hitching Post II restaurant in Buellton where the boys were to first meet Maya and Stephanie for dinner, Miles reacting to Jack’s “calm down” speech with the memorable line:

“If anyone orders Merlot, I’m leaving. I’m not drinking any f—–g Merlot!”

This sentiment was repeated often throughout the movie, seeing sales of Merlot plummet and sales of Pinot Noir soar in California!

One of my favourite pieces was Miles tutoring Jack at their first wine tasting:

“Let me show you how this is done. First thing hold the glass up and examine the wine against the light. You’re looking for color and clarity. Just, get a sense of it, OK? Uhh, Thick? Thin? Watery? Syrupy? OK? Alright. Now tip it. What you’re doing here is checking for color density as it thins out towards the rim. Uhh, that’s gonna tell you how old it is, among other things. It’s usually more important with reds. OK? Now, stick your nose in it. Don’t be shy, really get your nose in there. Mmm … a little citrus … maybe some strawberry … passionfruit … and, oh, there’s just like the faintest soupçon of like asparagus and just a flutter of a, like a nutty Edam cheese …”

After some discussion and a sympathetic evaluation of the wine just tasted, Miles gave Jack a puzzled look and asked:

“Are you chewing gum?”

To which Jack said “What? No! No …”

And, after a long-drawn-out pause, Miles responded: … “Spit it out.”

Sideways was obviously much more than an anti-Merlot vehicle, it reflected the affection of many for Pinot Noir. The Pinot discussion between Miles and Maya was one of the great verbal wine exchanges on film and was the highlight of the movie for me. You may remember Miles and Maya (Virginia Madsen) enjoying late night wine at Stephanie’s home (Sandra Oh) after that first dinner with the conversation going like this:

Maya: Can I ask you a personal question, Miles?

Miles: Sure.

Maya: Why are you so into Pinot? – It’s like a thing with you.

Miles: I don’t know. It’s a hard grape to grow. As you know. It’s thin-skinned, temperamental, ripens early. It’s not a survivor like Cabernet that can grow anywhere and thrive even when it’s neglected. No, Pinot needs constant care and attention and in fact can only grow specific little tucked-away corners of the world. And only the most patient and nurturing growers can do it really, can tap into Pinot’s most fragile, delicate qualities. Only when someone has taken the time to truly understand its potential can Pinot be coaxed into its fullest expression. And when that happens, its flavours are the most haunting and brilliant and subtle and thrilling and ancient on the planet. I mean, Cabernets can be powerful and exalting, but they seem prosaic to me, for some reason. By comparison. How about you?

Maya: What about me?

Miles: I don’t know. Why are you into wine?

Maya: I suppose I got really into wine originally through my ex-husband. He had a big, kind of show-off cellar. But then I found out that I have a really sharp palate, and the more I drank… the more I liked what it made me think about.

Miles: Yeah? Like what?

Maya: Like what a fraud he was.

Miles (laughs)

Maya: No, but I do like to think about the life of wine, how it’s a living thing. I like to think about what was going on the year the grapes were growing, how the sun was shining that summer or if it rained … what the weather was like. I think about all those people who tended and picked the grapes, and if it’s an old wine, how many of them must be dead by now. I love how wine continues to evolve, how every time I open a bottle it’s going to taste different than if I had opened it on any other day. Because a bottle of wine is actually alive … it’s constantly evolving and gaining complexity. That is, until it peaks … like your ’61 … and begins its steady, inevitable decline. And it tastes so f—–g good.

Miles (missing the implied invitation): Yeah.

One of the great wine conversations, I’m sure you’ll agree! And I’m certain you will have other favourite moments from the movie, probably including one of the last scenes where Miles drank his trophy ’61 wine from a poly-styrene cup alone in a fast food restaurant. And, given the quality of the wine, it probably still tasted good, even without company.

In the end Jack did marry his fiancée Christine (Alysia Reiner) in an Armenian ceremony and Miles and Maya finally got together. But while these events mark the end of the movie, the movie itself was all about Jack and Miles in the Santa Barbara wine country.

A Good Year

PICTURED ABOVE: BONNIEUX VILLAGE, PROVEVENCE

This was probably more of a mainstream movie given the people involved: director Ridley Scott (best picture Academy Award Gladiator), book Peter Mayle (A Year in Provence), cast Russell Crowe (best actor Academy Award Gladiator), Marion Cotillard (best actress Academy Award La Vie en Rose) and Albert Finney (nominated for five Academy Awards). Marc Klein’s screenplay created a charming movie in a lovely part of the world, Provence.

The plot based on Mayle’s book A Good Year has Max Skinner (Crowe) who, following the death of his parents, spent childhood holidays at his Uncle Henry Skinner’s vineyard in Provence. Max was a workaholic share trader in London who inherited the French property on the passing of his uncle (Finney) and travelled there to prepare for a quick sale. Once there he met some fascinating characters including a dedicated winemaker, Francis Duflot (Didier Bourdon) who made fine wine from illegal vines on the estate, bypassing France’s strict classification and appellation laws, his wife Ludivine Duflot (Isabelle Candelier), housekeeper at the château, Christie Roberts (Australian Abbie Cornish) a young Napa oenophile backpacking through Europe claiming to be Uncle Henry’s illegitimate daughter and Fanny Chenal (Marion Cotillard) a local café owner who Max caused to crash her bicycle and who became the love of his life.

A Good Year was largely filmed at Château la Canorgue near Bonnieux, a commune in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur region of southeastern France, approximately 30km east of Avignon. Fanny Chenal’s café was filmed at Hôtel le Renaissance in Gordes, about 10km northwest of Bonnieux.

I have chosen two sequences from the movie. The first was Max meeting Christie:

Ludivine: Monsieur Max!

Max: Yes?

Ludivine: There is, um … a person at the door.

Max: A person?

Ludivine: A person.

Christie: Bonjour.

Max: Bonjour. The only country that issues teeth like that is America.

Christie: Oh. You speak English.

Max: Like a native.

Christie: I’m Christie Roberts. I’m looking for Mr. Skinner.

Max: You lucky devil, you found him.

Christie: Impossible. You’re way too young.

Max: You know, I was just thinking the same thing about you.

Christie: I meant too young to be my dad. Henry Skinner is my father.

Ludivine: She has Henry’s nose. Allez. Allez.

Max: Wow. This is your mum?

Christie: In all her Flashdance glory. So, uh … is he around?

Max: Oh, Bollocks. Um … I’m sorry. I’ve forgotten your name.

Christie: It’s Christie.

Max: Christie. You see, Christie, um … Henry …

Christie: He’s dead, huh?

Max: A month ago. Um … Cup of tea? Yes?

My other choice was Max visiting Fanny to chat her up at her café and offering to help the busy waitstaff with service:

Max: Table six? Allez, allez!

Fanny: What are you doing?

Max: Don’t worry love, done this before.

Fanny: Where?

Max: Worked my way through university at London’s finest restaurants.

Fanny: Monsieur! Mais qu’est-ce qui se passe? (Sir! What’s going on?)

Max: Alors? Venez, monsieur! (So, come sir)

Fanny: Okay, okay. You can serve. But remember if there are any complaints, in France the customer is always wrong. Table six.

Max: Table six. Bonsoir … Table?

Local diner: Uh … 16

Max: Champagne?

Local diner: Yes., cheers.

Max: And what are we going to have here?

US diner 1: Garkin! Garkin! (a superficial and unsuccessful attempt to “speak the lingo?”) Get over here. I need, need help over here.

Max: En deux minutes, monsieur.

US diner 1: Where you going? Garkin!

US diner 2: Oh, do you speak American? ‘Cause this menu is all in French and we don’t understand it.

US diner 1: Yeah, we need some silverware.

US diner 2: But, uh, let me tell you what I would like to have. I would like a salad “Nicoisee …” with ranch dressing on it.

US diner 1: Wait, wait, baby, low-cal ranch dressing.

US diner 2: Oh, that’s right. I’m still on my diet. So, I would like low-cal ranch dressing with no oil. And could you sprinkle some bacon bits on top?

Max : (removing the menus and pointing to the exit): McDonald’s is in Avignon, fish and chips Marseille. Allez.

Several great one-liners for storing in the memory or for surprising people who forgot to see the movie in 2006. In the end Max forges an amendment to his uncle’s will that cedes the estate to Christie, who must work with Francis Duflot on the vineyard, and Max and Fanny rekindle their affection and fall in love which causes Max to choose Provence over London.

Bottle Shock

PICTURED ABOVE: CHATEAU MONTELENA, CALISTOGA, NAPA VALLEY

This 2008 movie was based on the now famous – infamous if you are French – 1976 Judgement of Paris wine tasting based on a short 7 June 1976 article in Time magazine and a 2005 book of the same name, both by George M. Taber. The movie was written by Randall Miller (Director), Jody Savin and Ross Schwartz.

The plot – based on the actual event – had Steven Spurrier (Alan Rickman) a British expatriate owner of struggling wine shop, Caves de la Madeleine and wine school Académie du Vin in Cité Berryer, a less than fashionable shopping arcade off the highly fashionable Rue Royale on the Right Bank in Paris’ ritzy First and Eighth arrondissements, trying to save his business by devising a wine-tasting with Californian wines against his favourite French wines that the French believed was no contest and heading to the Napa Valley to prepare.

George Taber (Louis Giambalvo), a reporter and editor with Time magazine, was the only reporter present at the historic event at the InterContinental Hotel, Paris. He wrote, “As this was … a blind-tasting (the judges) knew only that the wines were from France and California, and that the red wines were Bordeaux-style Cabernet Sauvignons and the whites Burgundy-style Chardonnays.” Winetasting protocol had the judges start with the whites.

The nine judges, all distinguished French wine people, were:

- Pierre Bréjoux (P. Gillain), Inspector General of the Appellation d’Origine Controlée Board which controls the production of the top French wines;

- Michel Dovaz, teacher of wine courses in French at the Académie du Vin;

- Claude Dubois-Millot (Phillipe Simon), sales director of GaulMillau, publisher of a leading French wine and food magazine;

- Odette Kahn (Marian Filali), editor Revue de Vin de France and Cuisine et Vin de France;

- Raymond Oliver, chef and owner Le Grand Véfour restaurant, founded in 1784, then a three-star now a two-star Michelin restaurant where Napoleon purportedly proposed to Josephine in 1796;

- Pierre Tari (Philippe Bergeron), owner of Château Giscours in Margaux, Secretary General of the Association des Grands Crus Classés, body of the 1855 classification;

- Christian Vannequé, head sommelier of La Tour d’Argent, then a three-star, now a one-star Michelin restaurant, founded in 1582 and possibly the most famous in Paris;

- Aubert de Villaine, co-owner of Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, one of France’s most prized vineyards; and

- Jean-Claude Vrinat, owner Taillevent restaurant, then a three-star now a two-star Michelin restaurant, a Paris dining newcomer in 1946.

Although nearly everyone can remember the winners of this tasting even if they can’t recall the second or third-placed wines, it is worthwhile recounting them here

- Chateau Montelena 1973 Chardonnay 132.0 points, 1429 Tubbs Lane, Calistoga, in the Napa Valley about 10km northwest of St. Helena CA, USA

- Meursault Charmes Roulot 1973 Chardonnay 126.5 points, Meursault, Côte de Beaune, Burgundy, France

- Chalone Vineyard 1974 Chardonnay 121.0 points, 32020 Stonewall Canyon Rd, Soledad, deep in Steinbeck country, Monterey County south of San Francisco, about 35 km southeast of Salinas CA USA (John Steinbeck’s boyhood home)

The red wine results were a lot closer:

- Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon 127.5 points, 6150 Silverado Trail, Napa, in the valley north of Napa. There are two wineries of the same name in the Napa valley, the red wine winner in Paris with a possessive apostrophe before the “s” (Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars), majority owned by Altira, previously Phillip Morris, and the other with a possessive apostrophe after the “s” (Stags’ Leap Winery), owned by Treasury Wine Estates

- Château Mouton-Rothschild 1970 Cabernet Sauvignon 126.0 points, La Pigotte, 33250 Pauillac, in the Medoc, 50km north-west of Bordeaux, France. In 1973 it became the only wine ever promoted from second growth to first growth in the 1855 classification and remains one of just five Premier Grand Cru Classé wines

- Château Haut-Brion 1970 Cabernet Sauvignon 125.5 points, another of the five Bordeaux Premier Grand Cru Classé wines, 135 Jean Jaurès, 33608 Pessac, Graves, France, about 2km southwest of Bordeaux

And because of the close scores we should add the fourth-placed red wine

- Chateau Montrose 1970 Cabernet Sauvignon 122.0 points, 3 Avenue des Vignolles, 33180 Saint-Estèphe, France, one of fourteen Duexiemes Crus wines in the 1855 classification, just north of Pauillac, close to Chateau Lafite-Rothschild there

The reaction of the judges ranged “from shock to horror”. No one had expected this, and the reverberations in France went on for years. But, of course, the Americans were both surprised and pleased. They had not expected this either. Having unknown American wines beat top quality Burgundy Chardonnays and First Growth Bordeaux Cabernets in a blind tasting conducted by experienced French wine judges was more than remarkable.

The event took place in Paris but most of the movie action was in California, around Chateau Montelena at Calistoga in the Napa Valley. There the fragile relationship of the struggling novice vineyard owner Jim Barrett (Bill Pullman) with his rebellious but ultimately business-saving son Bo (Chris Pine), his oenologically-gifted staff member Gustavo Brambila (Freddy Rodriguez), his oenologically- eager apprentice Sam Fulton (Rachael Taylor) and his unenthusiastic bank are all put to the test. Add a very proper Englishman Steven Spurrier to this mix and the suspicions he would have aroused in California regarding his motives for the tasting “I am English, and you are not” and you have a most enjoyable wine experience.

My first favourite moment was in the tavern where Bo challenges the patrons to bet that Gustavo can’t blind taste wine:

Bo: Hey, everybody, Listen up. Who here wants to wager a little money that this Mexican son of an immigrant field hand … can’t guess what kind of grapes are in these wines that our kind bartender has personally selected?

Patrons: (Spend some time discussing the potential of the bet)

Bo: Gentlemen, action if you want it. Put it on the bar.

Gustavo: It’s a cabernet.

Bartender: Yep.

Gustavo: 1971. Ridge. (Santa Cruz mountains, Cupertino, Palo Alto)

Bartender: Yep.

Patron: Let’s see the bottle. Oh, that’s nothin’ ! A recent vintage!

Gustavo: (swirling wine in mouth. Exhales). Dances like a lullaby at the tip of my tongue. Sonoma. Pinot noir. 1962 … Buena Vista. (Sonoma, Sonoma valley)

Bartender: Yep.

Patron: How does he do that?

Bo: Attaboy, Stav. Go get ‘em, baby.

Gustavo: It’s not from Napa. (Sniffing). I can’t tell you whether its merlot or cabernet. (Chuckles). Oh, dear God. I can’t say because … it’s a 1947 Cheval Blanc. About half merlot, half cabernet franc. (St-Émilion, Bordeaux)

Patron: Amazing! Ooh!

Bo: Yes! Thank you! Yes!

Gustavo: Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. Greatest wine ever made.

Then a tutorial with Jim and his apprentice, Sam:

Jim: Well, Sam, this is where wine is made, the vineyard. And the vineyard’s best fertilizer is the owner’s footsteps. It’s alluvial, sedimentary, volcanic soil.

Sam: Dry.

Jim: Right. You want to limit the irrigation ‘cause it makes the vines struggle … intensifies the flavor. A comfortable grape, a well-watered, well-fertilized grape grows into a lazy ingredient of a lousy wine. So, from hardship comes enlightenment. For a grape.

Steven (narrating): “Wine is sunlight … held together by water.” The poetic wisdom of the Italian physicist, philosopher and stargazer … Galileo Galilei. It all begins with the soil … the vine, the grape. The smell of the vineyard. Like inhaling birth. It awakens some … ancestral … some … primordial … anyway, some deeply imprinted and probably subconscious place … in my soul.

And finally, the great advice “goodbye” conversation between Gustavo and his boss Jim:

Jim: So, what did he think?

Gustavo: Excuse me?

Jim: The tea bag, the Brit. Did he like your wine? Come on, Gustavo. It’s a small valley. You think I wouldn’t find out?

Gustavo: I – I thought you’d be mad.

Jim: I am mad. You should have been straight with me.

Gustavo: I’d like for you to try it.

Jim: Nope. You’re on your own now kid.

Gustavo: Are you firing me?

Jim: I can’t afford you anyway.

Gustavo: Come on, Jim. What am I supposed to live on?

Jim: When your focus is elsewhere, you’re not a good employee. And your focus has been elsewhere for some time now.

Gustavo: You people. You think you can just …buy your way into this. Take a few lessons. Grow some grapes. Make some good wine. You cannot do it that way. All right, all right. You have to have it in your blood. You have to grow up with the soil underneath your nails … and the smell of the grape in the air that you breathe. The cultivation of the vine is an art form. The refinement of its juice is a religion … that requires pain … and desire and sacrifice.

Jim: Amen.

Gustavo: My father knew that. He was a field hand and he never had the opportunity to make his own wine.

Jim: I know that.

Gustavo: And I’m gonna make it happen one way or another.

You already know the outcome of this story. A sorry day for the French, a happy day for the Americans. As Steven Spurrier said to his friend and “almost” customer Maurice Cantavale (Dennis Farina) in the movie:

Steven: We have shattered the myth of the invincible French vine. And not just in California. We’ve opened the eyes of the world. And you know what I say?

Maurice: I say amen to that, brother.

Steven: You mark my words. We’ll be drinking wines from … well, South America. Australia. New Zealand. Africa. India. China. This is not the end, Maurice. This is just the beginning. Welcome to the future.

This may have been the start of wine’s future forty-four years ago. But that was the end of “Wine Flicks” for now.